What happened after N64’s launch? What happened with third-part support? What ultimately happened to the Nintendo 64?

What happened after N64’s launch? What happened with third-part support? What ultimately happened to the Nintendo 64?

——————————————-

With the wildly successful Nintendo DS and Wii hitting record sales month after month, Nintendo looks like a million bucks. All of Nintendo’s well calculated strategies and inventive risks look like–and may very well be–genius.

Going against the grain of more sophisticated machines such as the Xbox 360 and PlayStation 3, in 2006 Nintendo launched the Wii, a console less powerful than the original Xbox, accompanied by an un-tried game controller that smacked of trickery, and a name that sounded so close to urine that it made everyone over 10 years of age giggle.

But it wasn’t always that way.

“Looking Back at 1998: Nintendo’s Fall, Part 2” is the second part of a series originally published on Edge-Online.com.

——————————————

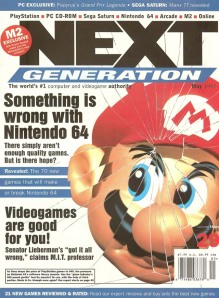

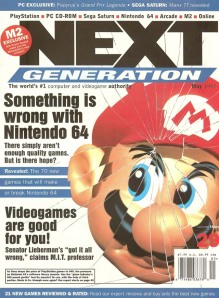

“Something is Wrong with Nintendo 64”

In the May 1997 issue of Next Generation (number 29, Volume 3), eight months after Nintendo’s successful launch with only two games, Next Generation magazine took a hard look at Nintendo’s system with the headline, “Something is Wrong with Nintendo 64,” followed by the subhead, “There simply aren’t enough quality games. But is there hope? Revealed: The 70 new games that will make or break N64.”

Next Gen compares the the Super NES launch titles to the Nintendo 64 launch titles. Super Mario World Vs Super Mario 64; PilotWings versus PilotWings 64; F-Zero versus Wave Race 64; and Actraiser versus Shadows of the Empire.

Those words were tough for Nintendo fans to face, but the cover image was even more jarring. It was illustrated with a picture of Mario’s face beneath a cracked plate of glass, splintering Mario’s smiling face into shards.

The basic premise of Next Generation’s feature article was Nintendo had promised “quality” ahead of “quantity,” but didn’t support that strategy with enough quality games. Additionally, the magazine wrote that the games that had arrived were:

1) “Out of date” (Doom 64, Cruis’n USA, NBA Hangtime, and Killer Instinct Gold among them).

2) “Too safe” (see previous list).

3) “And had all the flaws of cartridge-based games” (the lack of storage produced redundant textures, little to no FMV, and significant audio limitations).

4) NG also claimed that while Nintendo made a big deal about the power of 64-bit games over 32-bit games, “outside of Super Mario 64 and Wave Race 64, that extra power hadn’t meant squat to the quality of games. “

5) Finally, Next Generation claimed that there was “no third-party support.”

After two years of working at Next Generation, I headed up the first IGN site, N64.com, which launched in August 1996. The publisher of Next Generation Jonathan Simpson-Bint had given me the option to work on any of the IGN sites, and I had originally picked SaturnWorld.com. After some reflection, I decided to run the N64 site instead, shifting newly hired editor, Jeff Chen, to the Saturn site.

As the new editor at N64.com, I was conflicted. I took issue with Next Generation. Mainly, I disagreed with Next Generation’s review scores. The magazine had only given two Nintendo 64 games, Super Mario 64 and PilotWings 64, five out of five stars. Everything else was ravaged. Wave Race 64 received three stars? Wave Race 64 remains a brilliant piece of technology and gameplay even today. Despite a slew of jet ski games ushered out on PS2, none have been as good as Wave Race. Even the sequel Wave Race: Blue Storm wasn’t better the original. Turok: Dinosaur Hunter received only three stars? Didn’t that game have the coolest set of weapons ever? Even Mario Kart 64 received three stars.

As the new editor at N64.com, I was conflicted. I took issue with Next Generation. Mainly, I disagreed with Next Generation’s review scores. The magazine had only given two Nintendo 64 games, Super Mario 64 and PilotWings 64, five out of five stars. Everything else was ravaged. Wave Race 64 received three stars? Wave Race 64 remains a brilliant piece of technology and gameplay even today. Despite a slew of jet ski games ushered out on PS2, none have been as good as Wave Race. Even the sequel Wave Race: Blue Storm wasn’t better the original. Turok: Dinosaur Hunter received only three stars? Didn’t that game have the coolest set of weapons ever? Even Mario Kart 64 received three stars.

The conflict, however, was that even if I didn’t agree with Next Generation on a game-by-game basis, I agreed with Next Generation’s premise on the whole. On the whole, third-party games were lackluster, old, and safe. It wasn’t until one-plus year after launch that EA started supporting N64. And the 64-bit console’s power wasn’t vastly ahead of the competition, by any means.

All of my issues aside, the magazine’s criticisms pointed out N64’s biggest flaw: the cartridge model was already a thing of the past.

All of my issues aside, the magazine’s criticisms pointed out N64’s biggest flaw: the cartridge model was already a thing of the past.

The Medium Is the Message

“Numerous motivational factors explain why the third-part lineup thus far excels only in predictability,” reads Next Generation number 29, Volume 3. “One reason is directly linked to the Nintendo 64 business model which takes away a great deal of the profit potential for a third-party developer. Used to paying approximately $15 per disc for PlayStation, Saturn, and PC games, gamers pay about $35 for Nintendo cartridges and publishers must consider this carefully when planning games for the system.”

“‘From an inventory risk standpoint, we prefer working on CD platforms,’ admits Virgin Games’s Neil Young (in NG 29), which is part of the reason why Virgin is only developing one Nintendo 64 product as opposed to a number of games for competing CD-ROM systems. The bottom line is that when third parties have to pay Nintendo $35 up front for all the games they want to make, it requires a huge financial gamble.”

What happened to Battle Sport II and Contra 64? Why did we get Clay Fighter 63 1/3 and Dark Rift instead?

As we now know, Sony’s PlayStation usurped Nintendo as the market leader partially by wooing developers off Nintendo’s cartridge-based ideology. Developers and publishers alike were attracted to the possibilities of the CD-ROM, which provided more storage versus Nintendo’s cartridge storage capabilities, not to mention more flexible, less risky production scheduling. Publishers could store more video, art, and texture work required in the emerging 3D world of gaming on a CD than on a cartridge. And Nintendo’s rejection of the new technology (or at the very least misinterpretation of its power) played a major role in its stumble from the top.

Equally important to publishers were the economic issues involved with cartridges. There was no doubt in the mind of any smart executive that Nintendo would continue to be successful. Nobody had misgivings about the strength, brilliance, or popularity of Nintendo’s first-party games. Those would come and they would be great. Potentially they would open up sales, markets, and opportunities for third parties as well. Potentially.

How fun was Virgin's Freak Boy--a character that could turn into any weapon, instead of carrying it? And what is this, Ubisoft? Ed?

But the cartridge business all of a sudden looked riskier and far more expensive in comparison to the CD-ROM business. With cartridges–essentially individual chip sets plugged into the console–publishers had to guess how many cartridges to make in advance of the game’s release.

As many publishers had experienced with the NES and Super NES, guessing wrong on precise numbers (500,000 versus 900,000 units, for instance) could backfire in at least two ways. If they guessed short, they would have to queue up again to make more and potentially wait behind other publishers waiting to have their cartridges manufactured–and potentially lose sales during the waiting time. Publishers could miss the Christmas rush entirely if they guessed wrong.

Kirby Bowl transforms into Kirby's Air Ride. And of course, there is Mah Jong Master, wihch always threatened to arrive...

But if publishers guessed long and ordered too many, and customers didn’t buy as many as they had estimated, they would be stuck with extra, expensive cartridges. You always hear the real-life moral tale of Atari’s ET cartridges buried somewhere in the desert, but there is truth in that tale for all cartridge-based publishers. What do you do with thousands of pre-ordered cartridges that don’t sell? You could take Braid designer Jonathan Blow’s advice–to start at point zero and make a good game–but that’s easier said than done.

The PlayStation also touted 3D games with a hardware engine designed to create polygons and texture maps, not sprites. The Saturn, for instance, was a great sprite generating machine, and while the Nintendo 64 had serious power at the time, its storage and RAM limitations hampered the expanding demands gamers and developers were placing on better graphics and sound.

“[With CD-ROMs] publishers could provide more content without paying gigantic prices for memory,” explained Mike Mika, currently head of development at Other Ocean, and then soon-to-be associate editor at Next Generation. “No matter what size your game was, it was still just a single fixed cost. For Nintendo, you had a variety of cartridge sizes that became cost prohibitive very quickly. So you saw a lot of developers and publishers move to some exclusivity on PlayStation.”

Next Generation’s final argument in issue 29 crystallized the problem.

F-Zero, Zelda, and SIlicon Valley made it to N64, and all in great shape.

“Many software publishers are still smarting from huge losses on unsold cartridge games at the end of the 16-bit era, and the last thing they want to do is take another financial bath. So this means that no one wants to take any chances. Third parties will release only the safest, sure-fire winners for N64. And this, (when cemented by Nintendo’s demands for exclusivity which removes any profits from other versions) means tried-and-trusted no-brainer game recipes, big licenses, coin-op conversions–and a resounding ‘snore’ from experienced gamers.”

Square and the Third Party Problem

Square and the Third Party Problem

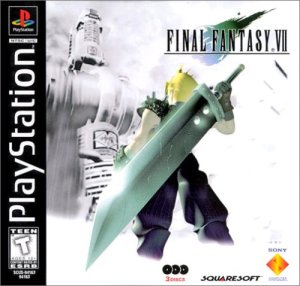

Squaresoft and Enix were two of the biggest RPG-making companies in Japan. On all visible fronts, both looked like staunch Nintendo supporters with Final Fantasy and Dragon Quest having sold millions of copies in Japan, Europe, and North America on Nintendo’s previous systems.

While Square and Enix originally had stated they would support Nintendo’s system, in retrospect those statements proved differently. It was more than significant to see Square and Enix embrace the PlayStation and then quietly and politely distance themselves from Nintendo’s N64.

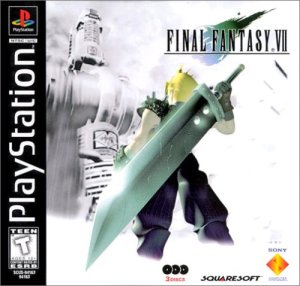

The biggest example was when Squaresoft’s Final Fantasy VII arrived on PlayStation in 1997. Sony Computer Entertainment America, which published the game in the U.S., proved its knack for marketing by positioning Final Fantasy VII as an action game in its TV commercials. The game, however, was anything but. Final Fantasy VII was a vast turn-based RPG with what seemed like hours of animated CG cutscenes. At the time, Squaresoft’s RPG was a remarkable visually stunning, and epic game. It sold millions of copies on PlayStation. If you were system agnostic, you bought your PlayStation and you were too were delighted. But to any Nintendo purist, Square’s FFVII on PlayStation felt like betrayal.

“The move by Square to CDs was very significant,” said Chris Charla, currently the VP of business development at Foundation 9 Entertainment, and former Editor-in-Chief of Next Generation Magazine. “First, it gave us a hint that Sony’s system might have some staying power… Seriously, it was really the ultimate seal of approval for optical media in games, and of course it marked a shift by third parties towards PlayStation as the system of choice.”

“It really made people understand what CD offered over cartridge,” added Mika. “There was no way that Nintendo could compete with the imagery and animation that Square put into Final Fantasy VII. People who were just starting to wake up to the next generation of gaming would look at FFVII and Zelda and see that FFVII was just simply a higher impact visually. It was in effect the better ‘book cover.’ And as far as marketing goes, that’s what you need to win people over. It looked better in commercials, screenshots, etc. Its brilliant use of FMV combined with real-time 3D was stunning.”

Brilliance and the Slow Decline

In winter 1997, early hardware and software sales figures indicated that despite Nintendo’s late entry into the marketplace with the Nintendo 64 (Nintendo switched the name from Ultra 64 many months after the Shoshinkai Exposition), the Redmond, Washington-based company had come out fighting.

According to TRST data (The Toy Retail Tracking System), an independent tracker of software sales, six of the 1996 holiday season’s best selling titles were Nintendo 64 titles. Those games included the season’s number one selling game, Super Mario 64, Star Wars Shadows of the Empire (#3), Killer Instinct Gold (#5), Cruis’n USA (#6), Wave Race 64 (#8), and Mortal Kombat Trilogy (#9). Super NES games Donkey Kong Country 2 and Donkey Kong Country 3 also made the top 10, leaving one Saturn and one PlayStation game in the top 10.

As Nintendo’s system built momentum, there were some key third-party titles: Konami’s International Superstar Soccer (AKA Pro Evolution or Winning 11), Midway’s Top Gear Rally, and a few others. Several elements kept N64 relatively close in the market race, but third-party support and consistent quality games were rarely part of the equation.

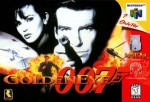

Second-party developer Rare, however, emerged into a powerhouse force during the N64 years. Best known for early hits Battletoads and Jetpac, and Super NES hits Donkey Kong Country 2 and 3, Rare hit its stride with N64, producing creative hits such as Blast Corps, breaking movie-game stereotypes with the first genuinely good console first-person shooter, GoldenEye 007, and producing clutch games such as Diddy Kong Racing for the otherwise empty Christmas holiday of 1997. Additional Rare hits included Donkey Kong 64, Jet Force Gemini, Perfect Dark, and what many critics consider Rare’s best game, Conker’s Bad Fur Day.

Second-party developer Rare, however, emerged into a powerhouse force during the N64 years. Best known for early hits Battletoads and Jetpac, and Super NES hits Donkey Kong Country 2 and 3, Rare hit its stride with N64, producing creative hits such as Blast Corps, breaking movie-game stereotypes with the first genuinely good console first-person shooter, GoldenEye 007, and producing clutch games such as Diddy Kong Racing for the otherwise empty Christmas holiday of 1997. Additional Rare hits included Donkey Kong 64, Jet Force Gemini, Perfect Dark, and what many critics consider Rare’s best game, Conker’s Bad Fur Day.

Ocean didn't want us to reveal that Mission Impossible's lead character had a face that merged John Travolta's and Tom Cruise's, due to Cruise's refusal to use his likeness in the game.

The supreme irony of Nintendo 64’s decline in sales and support was that Shigeru Miyamoto’s most transforming, innovative, and visionary work was done on N64. Today, Super Mario 64 remains one of the greatest games ever because of Miyamoto’s ability to successfully bring Nintendo’s flagship franchise into the 3D realm while remaining true to the original. In Mario 64, Miyamoto addressed and, in most cases, solved the difficulty that plagued many developers years after–the 3D camera.

Zelda shows us what it means to target with a Z.

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time was even more visionary. Aside from introducing key innovative mechanics (which are staples in game mechanics today) such as Z-targeting (some might argue this same technique was simultaneously introduced in Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver), and contact sensitive actions, Ocarina of Time evolved story-telling techniques by jumping in time and portraying Link as both a young and grown character. The time-jumping technique also delivered real consequences to earlier actions made in the game. Other clever innovations involved the use of the ocarina. The ocarina had an extraordinary emotional effect on players who had to memorize tunes, which then cast magic on characters and items, enabling Link to progress.

Next Generation called Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time the “game of the century,”‘ under Charla’s editorial direction. Future’s sister publication in England, Edge, in 2007 reported Ocarina of Time as the “best game of all time,” according to its reader poll.

The 64DD did arrive, but in limited supply.

But even Nintendo had problems with how to deliver The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time to its cartridge system. The Bulky Drive, later known as the 64DD, was originally planned as the defacto peripheral on which the game would arrive. But the 64DD (1999) arrived after Ocarina of Time (1998), and never took off. Nintendo, instead, doubled the size of its cartridge to 32 MBs and fit Zelda onto it, the biggest cartridge Nintendo had ever created.

Well before Nintendo 64’s five-year cycle had come to a close, the Nintendo 64, despite an impressive start and significant first- and second party games peppering its lifespan, continued to lose significant market share to Sony while third-party support dropped precipitously. By 1999, when the Dreamcast shipped, even companies like Midway and Acclaim, original members of the “Dream Team,” stopped supporting N64.

Sony’s win with the PlayStation was due to a combination of factors. First, Sony bet on the right storage medium. Equally important, however, was that Sony had earned market leadership by wooing and grooming third-party publishers who created a massive library of games that reached into all genres and sub-genres. It created its own first- and second-party hits such as Gran Turismo, Crash Bandicoot, Spyro the Dragon, Twisted Metal, JetMoto, and NFL GameDay, to name just a few. But one could question that if Nintendo, despite all its creative strides in software, had picked a different, better technology, the 32-bit generation console wars would have emerged much differently.

Yuke Yuke Troublemakers was a weird a wonderful game, just like all of Treasure's game.

How would Nintendo take these lessons and apply them to its next system, the GameCube? And how would Nintendo build upon Rare’s second-party strategy? And how would technology ultimately be the issue that Nintendo would tackle in a totally unique way? Look for part 3 of “Looking Back: Nintendo’s Fall” soon.

What happened after N64’s launch? What happened with third-part support? What ultimately happened to the Nintendo 64?

What happened after N64’s launch? What happened with third-part support? What ultimately happened to the Nintendo 64?

As the new editor at

As the new editor at  All of my issues aside, the magazine’s criticisms pointed out N64’s biggest flaw: the cartridge model was already a thing of the past.

All of my issues aside, the magazine’s criticisms pointed out N64’s biggest flaw: the cartridge model was already a thing of the past.

Square and the Third Party Problem

Square and the Third Party Problem

Second-party developer Rare, however, emerged into a powerhouse force during the N64 years. Best known for early hits Battletoads and Jetpac, and Super NES hits Donkey Kong Country 2 and 3, Rare hit its stride with N64, producing creative hits such as Blast Corps, breaking movie-game stereotypes with the first genuinely good console first-person shooter, GoldenEye 007, and producing clutch games such as Diddy Kong Racing for the otherwise empty Christmas holiday of 1997. Additional Rare hits included Donkey Kong 64, Jet Force Gemini, Perfect Dark, and what many critics consider Rare’s best game, Conker’s Bad Fur Day.

Second-party developer Rare, however, emerged into a powerhouse force during the N64 years. Best known for early hits Battletoads and Jetpac, and Super NES hits Donkey Kong Country 2 and 3, Rare hit its stride with N64, producing creative hits such as Blast Corps, breaking movie-game stereotypes with the first genuinely good console first-person shooter, GoldenEye 007, and producing clutch games such as Diddy Kong Racing for the otherwise empty Christmas holiday of 1997. Additional Rare hits included Donkey Kong 64, Jet Force Gemini, Perfect Dark, and what many critics consider Rare’s best game, Conker’s Bad Fur Day.